WELLNESS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR COUNSELOR EDUCATION AND COLLEGE STUDENT INTERVENTION

HOLLINGSWORTH, MARY ANN

UNIVERSITY OF WEST ALABAMA

COLLEGE OF EDUCATION

DEPARTMENT OF INSTRUCTIONAL LEADERSHIP AND SUPPORT

Dr. Mary Ann Hollingsworth

Department of Instructional Leadership and Support

College of Education

University of West Alabama.

Wellness as a Framework for Counselor Education and College Student Intervention

Synopsis:

This study assessed needs of both students in counselor training and entering freshmen in overall wellness through use of an assessment and intervention within a wellness paradigm The Personal Wellness Questionnaire and Plan developed from this study supports use of wellness assessment and planning as tool for work with college students and graduate students training to be counselors.

Wellness as a Framework for Counselor Education and College Student Intervention Mary Ann Hollingsworth University of West Alabama

Dr. Mary A. Hollingsworth is an assistant professor at the University of West Alabama. She has 15 years of experience as a counselor with populations across the life span as well as settings of academia, community mental health, and primary health care. Her primary research interests and innovative work have been with counseling and college student work through a paradigm of wellness.

Abstract

Literature supports the use of wellness as a framework for counselor training and intervention with college students. Wellness models provide foundation for work in six areas: emotional, intellectual, physical, social, spiritual, and work. Two additional wellness areas, financial management and time management, are included. This study assessed needs of both students in counselor training and entering freshmen in overall wellness through use of an assessment and intervention within a wellness paradigm The Personal Wellness Questionnaire and Plan developed from this study supports use of wellness assessment and planning as tool for work with college students and graduate students training to be counselors.

Wellness is part of the definition of counseling: “Counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families, and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (as cited in Meyers, 2014, p. 33). Meyers (2014) noted that wellness has been a core part of the counseling profession throughout its history, with increased concurrent interest as the term has become somewhat of a fad among different professions and even in pop culture.

The realms of graduate study and counselor preparation provide much information on application of a wellness paradigm for counseling practice. Graduate students are often representative of clients or students whom counselors assist in that many of them experience life events for which counseling might be sought. These life events integrate with the multiple components of wellness. As the counseling profession more deeply embraces a paradigm of wellness for practice, this focus is also increasing in counselor preparation.

Wellness Components

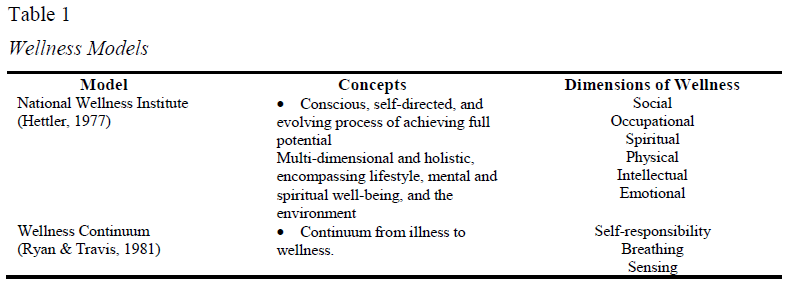

Several wellness models include multiple components. These models are National Wellness Institute (Hettler, 1977), Wellness Continuum (Ryan & Travis, 1981), High Level Wellness (Ardell, 1986), and The Indivisible Self (Myers & Sweeney, 2005).

A synthesis of the models defines wellness as a state of the totality of a person’s life as mind, body, and spirit interacting with environmental contexts. Throughout life, an individual moves along a continuum from illness to wellness through personal choices and action. Myers and Sweeney have led much of the effort throughout the counseling profession to frame counseling within the paradigm of wellness. Myers and Sweeney (2008) noted that a wellness orientation provides for a strengths-based approach that can maximize human growth and development. This approach supports prevention efforts with clients, students, and future counselors-in-training that may lessen decline in mental health and strengthen capacity for coping when life’s challenges occur. Common dimensions across the models are social, occupational (which could be considered school work for children), spiritual, physical, intellectual, emotional, and environmental.

Additional components that warrant inclusion for assessment and intervention within a counseling paradigm of wellness are finances and time management. Carney and Savitz (1980) conducted a study with 800 university students and 400 university faculty to ascertain the most common areas of concern for which students would self-refer or be referred by faculty to the university counseling center for assistance. Of the 14 concerns noted, faculty rated finances as the second most common problem and students rated this as the third most common problem.

Financial Wellness

Ronzio (2012) examined the concerns of adult women in the midst of career transitions and found financial security to be a critical factor in the successful management of a career transition. Ronzio noted that much of the counseling time spent with an adult woman making a career transition should focus on assessment of, and planning for, financial management skills and stability. Sauerheber and Bitter (2013) noted the benefit of addressing contextual factors with an engaged couple such as rules and expectations of each person about management of finances.

Financial wellness counseling support is needed both in university and community settings for veterans and their families. Elbogen, Sullivan, Wolfe, Wagner, and Beckham (2013) discussed multiple ways in which these individuals can encounter challenges with financial stability after leaving military service. They also noted that “military experiences can uniquely affect financial well being” (p. 248). Elbogen et al. found that military members may not have learned to budget while in the military due to the provision of housing, rations, and health care. Additionally, multiple deployments may have an adverse impact on financial security for a service member and family. Successful financial wellness in life after the military involved attainment of financial literacy.

Wellness in Time Management

Langberg, Epstein, Becker, Girio-Herrera, and Vaughn (2012) studied an intervention targeting organization and planning skills of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These authors included management of time in the scope of organization skills, such as planning ahead to have adequate time for academic study and management of time during and after school. The study assessed time management skills and training and encouraged practice with planning and time management.

Scanlon, Bundy, and Matthews (2010) conducted a study that hypothesized measures of meaningful time use would contribute to a prediction of psychological health. They noted that general results in research on time structure and psychological health indicated significant positive associations. Scanlon et al. surveyed 150 unemployed 18- to 25-year old Australians on meaningfulness of time use and health. Study results supported the importance of meaningful time use, especially in reasoning for an activity, in overall health with a person in unemployment.

Wellness Framework for Work with Students

Wolf, Thompson, Thompson, and Smith-Adcock (2014) conducted a study with a semester long student-led wellness program for graduate students in counselor education. This program included both training in wellness practices and implementation of additional wellness activities in daily life. Study findings indicated that student knowledge and practice of wellness increased. Lenz, Sangganjanavanich, Balkin, Oliver, and Smith (2012) also studied the use of a wellness model of supervision for graduate students in a counseling internship and noted that participants increased awareness of wellness and developed counseling skills within this framework that were comparable to students under other models of supervision.

Some counselor training programs include opportunities to earn practicum or internship hours with undergraduate students through their own university counseling center or a departmental counseling lab. As with graduate students, undergraduate students experience a myriad of issues that warrant counseling support. These include daily life skills needs, as well as needs per a mental illness diagnosis.

Increasing Need for Wellness Education

Jodoin and Robertson (2013) noted empirical evidence that college students are coming to campus with more severe psychology concerns than in the past. This has an impact on traditional entry into college as a freshman and also on interventions such as suicide prevention. These authors noted the need for suicide prevention that goes above and beyond the traditional medical-based treatment models. Jodoin and Robertson discussed the Jed Foundation and the Suicide Prevention Research Center research-based model of comprehensive suicide prevention, which is integrated within the SAMSHA Suicide Prevention grant directives currently being implemented at the University of West Alabama. Two components of this model are also components of wellness: Develop Life Skills and Promote Social Networks.

Technology and Wellness Education

The increase of technology has provided an optimal opportunity to promote wellness education and practices for college students in a flexible and user-friendly format. Quartiroli and Zizzi (2012) noted the tendency for entering college students to acquire habits that can lessen overall health and wellness such as gaining the “Freshman 15.” They conducted a study of an 8-week intervention program that was delivered via the Internet. Study results indicated efficacy in institutional provision of preventive services in wellness as a part of the transition to college life. This also presents opportunity for counselors-in-training to develop interventions for their own universities.

Method

This study assessed use of an author-developed assessment, planning, and management instrument(Personal Wellness Questionnaire and Plan – PWQP) to help entering freshman increase awareness of overall wellness and how they could be pro-active in management of that while in college. The study also included use of this instrument as a foundation for graduate students in counselor education on ethical self-care and practice of counseling skills. A convenience sample of current students in a freshman orientation course graduate counselor education students was used for this study. As both groups can represent general adult populations, results of this study could provide a foundation for further study with additional populations.

This study was approved by the University of West Alabama Institutional Review Board.and consisted of two research questions. Research question one “How does a wellness paradigm promote effective self awareness and action in total personal wellness for students?” Research question two was “How does a wellness paradigm promote training in counseling skills?” 67 freshman over three semesters used the Personal Wellness Questionnaire and Plan as a part of their Frehsman Orientation Course as taught by the author. Eighty-one students in five classes engaged in skills practice during each class session with a classmate partner or worked with a volunteer child or adolescent to increase awareness and develop skills for personal wellness.

Participants

Freshman Orientation.The PWQP was used in three courses in Freshman Orientation, two spring semester courses and one fall semester course. A total of 67 students participated, with22 % male and 78 % female; 54 % of the students were Black, 45% of the students were white, and less than one % were other. 11 % of the students were over the age of 25. All other students were 18 – 25 years of age.

Graduate students in counselor training.The PWQP was used in five graduate courses in counseling and psychology as a framework for skills training and practice. These courses were two sections of Counseling Theories and Techniques, two sections of Counseling Children and Adolescents, and one section of Therapeutic Relationships. A total of 81 students participated with 12.3% male and 87.7% female; 87.7% of the students were Black and 12.3% of the students were White. Ages represented were 2.4% were 18–25 years old, 70.4% were 26–35 years old, 23.5% were 36–50 years old, and 3.7% were over 50 years old.

Instrumentation

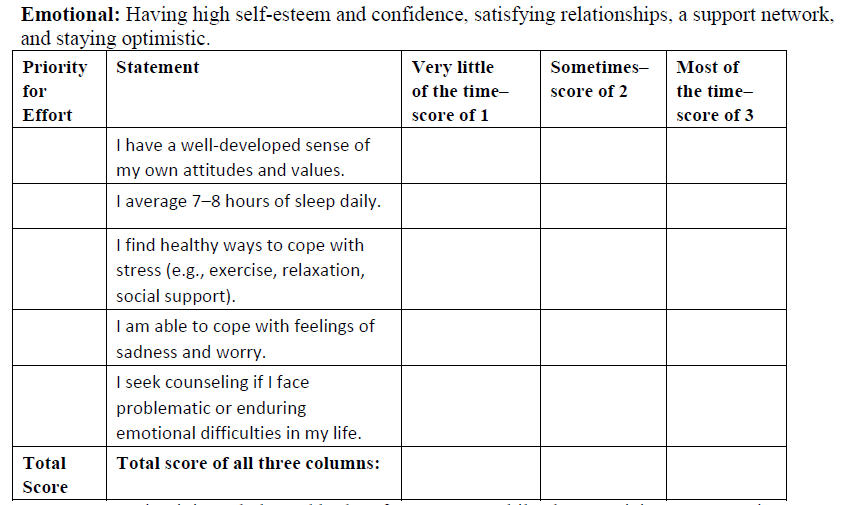

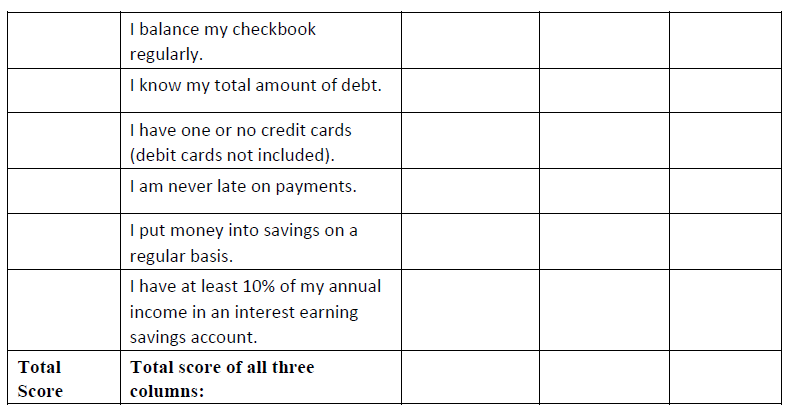

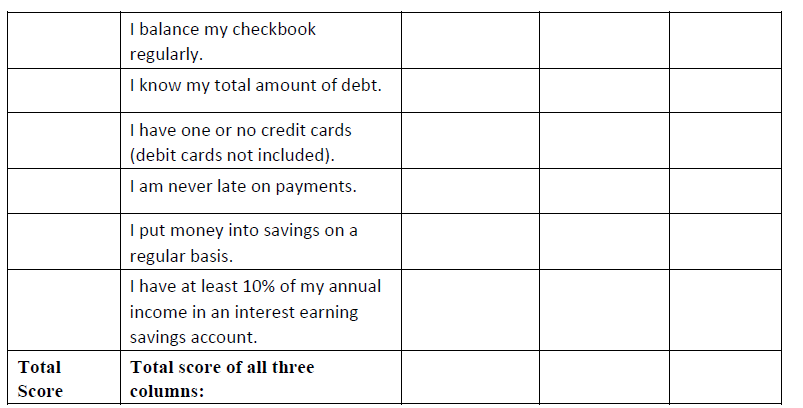

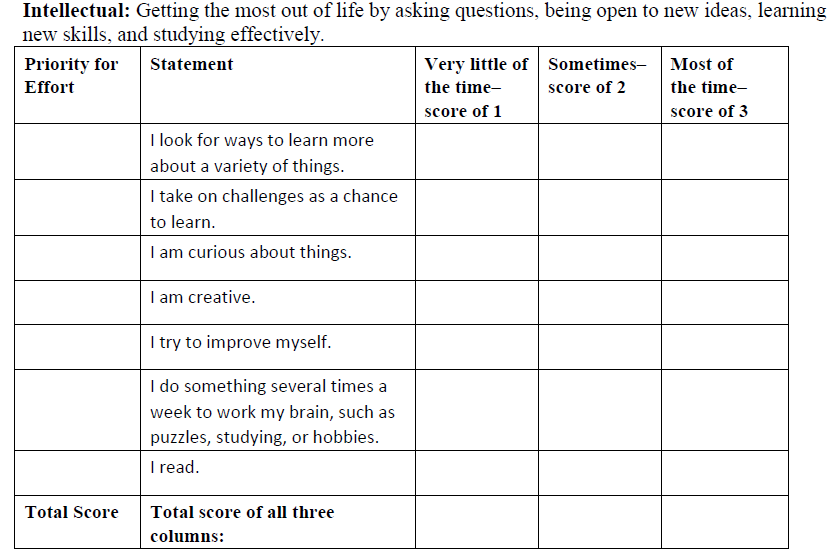

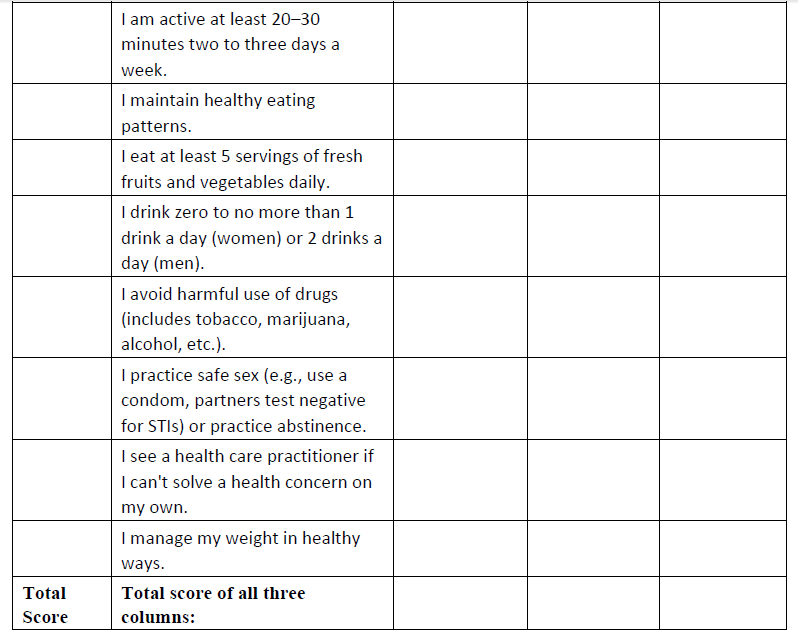

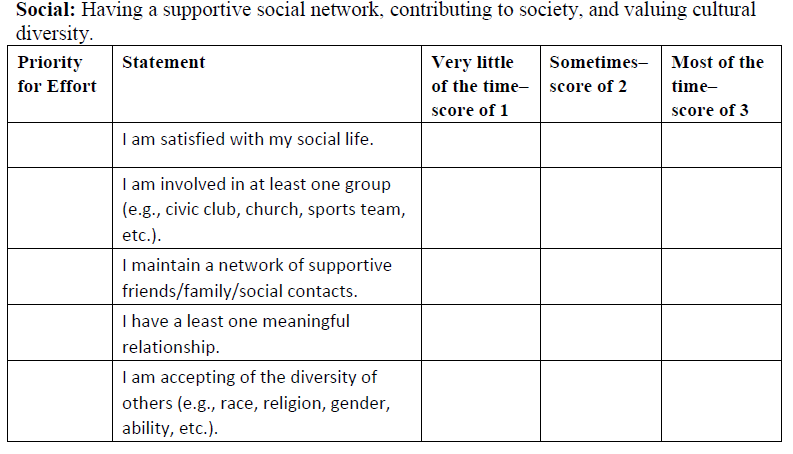

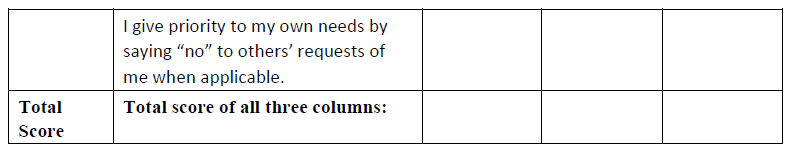

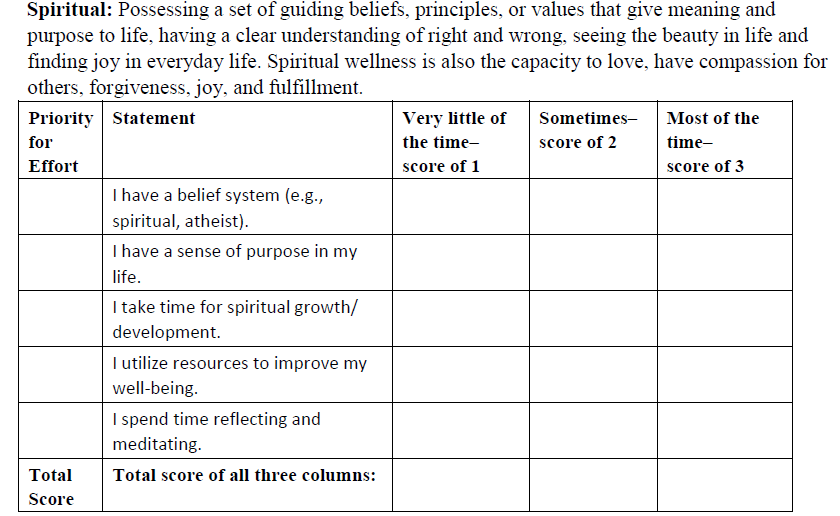

The PWQP was used for students in both groups. The PWPQ has three components. Participants first responded to items in each of eight areas of wellness to indicate to what degree that statement fit them. The eight areas of wellness are Emotional, Financial, Intellectual, Physical, Social, Spiritual, Time Management, and Work. Then participants went back and indicated priority for effort to work on wellness areas in which they did not currently have as high a level of positive practice. The third component consisted of writing a follow-up plan to address their priority needs for wellness work. This instrument is provided at Appendix A.

Procedures

Freshman Orientation.Students in Freshman Orientation engaged in class and online discussion about their progress with wellness needs. At the beginning of the course, students completed PWQP. Class discussion consisted of the instructor reviewing information about the different areas of wellness and giving students opportunity to share progress and helpful information they had for other students. A discussion forum was also set up in Blackboard for each of the eight areas of wellness for students to engage in each week. Students were required to participate in each forum through sharing a resource and what they helpful about that resource. At the end of the course, students wrote a short essay to describe their overall progress in working on their personal wellness.

Graduate students in counselor training.Students in the Counseling Theories and Techniques class and the Therapeutic Relationships class engaged in skills practice during each class session with a classmate partner in which they applied content focus for the respective class. Students worked with the same partner throughout the course and each class’s skills practice included role play as the counselor and the client. Each class member was free to share the concern from the individual PWQP that he or she would like to work on in the skills practice. In Counseling Theories and Techniques, students were asked to practice techniques per the theory of study in the respective class session. Examples were, use of “free association” with the psychoanalytic approach and use of the “exception question” with solution-focused therapy. In Therapeutic Relationships, students were asked to practice the focus skills studied in that respective class session. For example, one class focused on the skills of probing and summarizing and another class focused on goal setting.

Students in Counseling Children and Adolescents were asked to work with a volunteer child or adolescent to increase awareness and develop skills for personal wellness. As this course focused on application of counseling theories to work with children and adolescents, these students selected a theoretical framework within which to work with their volunteer. They first obtained written permission from the volunteer and caregiver for participation in the project. Then they conducted a personal wellness assessment that was a modification of the PWQP to fit younger participants. From this assessment, they worked with the volunteer to select an area of wellness to work on for 6 weeks of the course. Course students met with the volunteer on a weekly basis and used their chosen theoretical approach to assist their volunteer to make the desired wellness improvements.

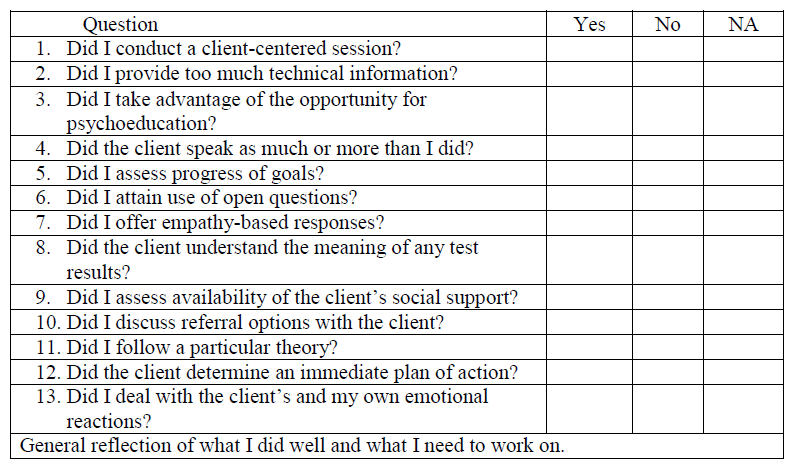

Students in all classes maintained a portfolio throughout the course that included the initial assessment of wellness for self or a volunteer, a weekly journal entry that described and assessed the skills practiced and outcomes, and a final paper that provided summary of the work throughout the course in skills practice, progress on goals accomplishment, and reflection on what was learned and what was still needed to continue progress initiated in the intervention started in the course. Table 3 is a copy of the weekly self-assessment for students in Therapeutic Relationships.

Results

Students in Freshman Orientation shared results of this work on wellness through both interaction in their Blackboard discussion forums and end of course essays on overall progress on personal wellness throughout the course. These essays indicated increased awareness in areas that were important to their wellness. Students also indicated intent to continue monitoring their self-care, especially in physical wellness.

Graduate counseling students indicated how self-awareness on wellness had progressed through their end of course reflection paper. In the two classes on Theories and Techniques, the final assessment on competency in skill usage was a student demonstration in which each student randomly drew a skill to practice in a given scenario in which a classmate role-played the client; 67% of the students were able to correctly use the randomly drawn skill with their client role model. In the two classes on Counseling Children and Adolescents, students were required to demonstrate a skill of their choice that they had used with their volunteer. Some students provided a video of the specific activity and some students led the class in an activity. All students demonstrated correct application of the skill chosen. In the class on Therapeutic Relationships, students submitted a weekly journal in which a self-assessment was provided on skills usage. These indicated that most students grew in appropriate use of skills as they answered the self-assessment questions each week. Students in all classes indicated efficacy of the wellness framework for learning skills through comments with their end of course evaluation through an overall rating of 3.73 in agreement with the statement “I have become more competent in this area due to this course. Individual student comments included perception of benefit in learning “how to become a counselor and what & how to say something to a person in need, practical application of course content, and the self-assessment portion of the class.

Discussion

Previous research provides support for the use of wellness as a framework in counseling and in counselor training. Wellness models previously provided foundations for work with clients in issues for six areas of emotional, intellectual, physical, social, spiritual, and work wellness. Assessment of needs in this study indicated additional wellness concerns in the areas of financial management and time management. A literature review on these areas supported inclusion of these two areas in a wellness framework for counseling. Further research is needed to clarify the significance of these as part of a wellness paradigm for counseling. Surveys of graduate students, graduate faculty, and the work done by participants in this study indicate an opportunity for counselors to assist their clients in both problem prevention and problem resolution through a wellness framework of practice. The Personal Wellness Questionnaire and Plan protocol from this study supports use of wellness assessment and planning as an intervention in work with clients toward whole person wellness.

While this study included only students at a small regional university in West Alabama, further study in other settings would strengthen the knowledge base on usefulness of a wellness paradigm for counseling. Further study is needed on inclusion of financial management and time management as components of a wellness paradigm for counseling. Further study would especially be helpful on application of wellness assessment and intervention within counseling practice. Finally, this study supports the need for continuing advocacy of counselors to promote practice that is rooted in promotion of whole personal wellness for self and clients. The study also supports the need for institutions of higher education to promote total personal wellness awareness and practice with students from entering freshmen throughout college careers.

References

Ardell, D. B. (1986). High level wellness: An alternative to doctors, drugs, and disease. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

Carney, C. G., & Savitz, C. J. (1980). Student and faculty perceptions of student needs and the services of a university counseling center: Differences that make a difference. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27(6), 597–604.

Elbogen, E. B., Sullivan, C. P., Wolfe, J., Wagner, H. R., & Beckham, J. C. (2013). Homelessness and money mismanagement in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 248–254. doi:10.2405/ AJPH.2013.301335.

Hettler, B. (1977). Six dimension model. Stevens Point, WI: National Wellness Institute.

Jodoin, E. C., & Robertson, J. (2013). The public health approach to campus suicide prevention. New Directions for Student Services, 4, 15–25.

Langberg, J. M., Epstein, J. N., Becker, S. P., Girio-Herrera, E., & Vaughn, A. J. (2012). Evaluation of the homework, organization, and planning skills (HOPS) intervention for middle school students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as implemented by school mental health providers. School Psychology Review, 41(3), 342–364.

Lenz, A. S., Sangganjanavanich, V. F., Balkin, R. S., Oliver, M., & Smith, R. L. (2012). Wellness model of supervision: A comparative analysis. Counselor Education & Supervision, 51, 207–223.

Meyers, L. (2014). In search of wellness. Counseling Today, 56(9), 32–40.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (Eds). (2005a). Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2005b). The indivisible self: An evidence-based model of wellness. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 61(3), 269–279.

Myers, J. J., & Sweeney, T. L. (2008). Wellness counseling: The evidence base for practice. Journal of Counseling and Development, 86, 482–494.

Quartiroli, A., & Zizzi, S. (2012). A tailored wellness intervention for college students using internet-based technology: A pilot study. International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 15, 37–50.

Ronzio, C. R. (2012). Counseling issues for adult women in career transition. Journal of employment counseling, 49, 74-85.

Ryan, R. S., & Travis, J. W. (1981). Wellness workbook. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

Sauerheber, J. D., & Bitter, J. R. (2013). An Adlerian approach in premarital counseling with religious couples. The Journal of Individual Psychology, 69(4), 305–327.

Scanlon, J. N., Bundy, A. C., & Matthews, L. R. (2010). Investigating the relationship between meaningful time use and health in 18- to 25-year-old unemployed people in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20, 232–247.

Wolf, C. P., Thompson, I. A., Thompson, E. S., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2014). Refresh your mind, rejuvenate your body, renew your spirit: A pilot wellness program for counselor education. Journal of Individual Psychology, 70(1), 57–75.

Appendix A

Personal Wellness Questionnaire & Plan

Whether the major focus of your life is being a student, working a job, or enjoying your retirement, there are multiple areas of your life that contribute to the success of your major focus. Those areas together make up your personal wellness.

The purpose of this questionnaire is to indicate your current profile of overall wellness and to help you plan a foundation from which to build and strengthen your different areas of personal wellness to better support the major focus of your life.

INSTRUCTIONS:

In each of the following 8 components of personal wellness, please indicate how often the following statements apply to you. For the total score for each component, add up the columns and enter the total of those.NOTE: Adults were asked to complete the form with pen. Children and adolescents completed this verbally as they were read the statements and asked to indicate which category applied to them—Very little of the time, Sometimes, or Most of the time. Statements were indicated as Not Applicable with children and adolescents if the item did not apply to them at that time. An example would be if a child did not have a credit card.

TOTAL WELLNESS SCORE:Add up your scores for all 8 components of wellness to give you your total wellness score.

PRIORITY FOR EFFORT:It is common for people to have some areas in which they are well much of the time, some areas in which they are well some of the time, and some areas in which they are well very little or none of the time. As you look back at your scores in the different areas, note the areas in which you indicated “very little of the time.” Pick one of these in each of the 8 wellness components to prioritize your efforts for improvement. If you were well enough in a component that your lowest scores were “sometimes,” then choose one of these response areas as a priority for attention.

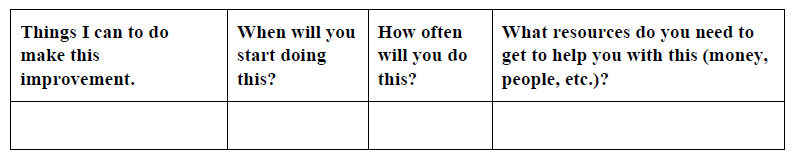

NOW you are ready to develop your Personal Wellness Plan. FOLLOW-UP PLAN: Complete the following for each priority area that you indicated.

Area to work

ON: