AN ANALYSIS OF ING-FORM AND IT’S APPLICATION TO ENGLISH EDUCATION

ITO, HAYATO

SHINSHU UNIVERSITY, JAPAN

FACULTY OF ARTS.

ITO, HAYATO

SHINSHU UNIVERSITY, JAPAN

FACULTY OF ARTS.

An Analysis of ing-form and its Application to English Education

Synopsis:

Japanese learners of English have difficulties in fully mastering the usages of –ing form. This presentation will examine the mistakes of using –ing form made by Japanese EFL learners, and through such analysis, we will seek to find a better pedagogy in teaching –ing form to Japanese EFL learners.

An Analysis of –ing Form and its Application to English Education

Hayato Ito, Shinshu-University, Faculty of Arts

1. Introduction

In Japanese English education, we are taught progressive form, present participle and participial construction as the –ing form. Japanese EFL students have difficulties in fully mastering these usages. In this analysis, we will pick up participial construction.

According to Sugiyama (1998), participial construction is similar to Japanese vague expression “~shite” because participial construction is expressed without conjunction which specifies the relation between main clause and participle clause. However, we cannot declare that English native speakers and Japanese students use participial construction in the same situation. We would like to clarify the difference of using the participial construction between native speakers and Japanese students.

In this paper, our concern is to consider participial construction with present participle. We are not concerned here with the past participle. In the next chapter, we will examine previous studies.

2. Previous Studies

2.1. Langacker (1991)

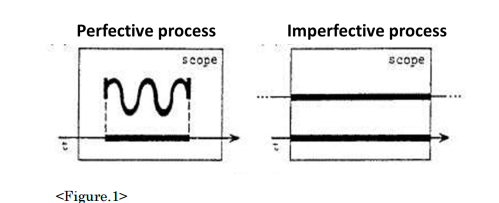

Langacker (1991) showed the classification of verbs. Verbs can be classified into perfective process and imperfective process. The perfective process is specifically bounded in time. In contrast, the imperfective process is not bounded in time and the component states don’t change through time. (Figure.1)

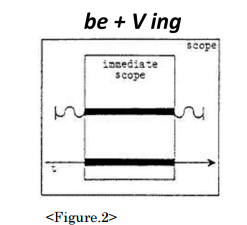

He also studied the problem of progressive form. He emphasizes that the function of progressive form is imperfectivizing. By adding be…-ing, we exclude the beginning and the ending of the action and focus on the homogeneous internal state. This is the concept of progressive form developed by Langacker. To take a simple example, in contrast to She examined it, which designates a complete act of examination and specifies its past occurrence, She was examining it merely indicates that such act was under way. (Figure.2)

In addition, Langacker (2008) applied this concept to the present participle. The beginning and end of the verbal process lie outside the immediate temporal scope, which delimits the relationship profiled by the participle.

The foregoing argument would be accepted by most people, but it leaves unanswered certain aspects of the participial construction. I will show you another study which is concerned with participial construction.

2.2. Hayase (1992)

Hayase(1992) studied the problem of participial construction. She examined each type of participial construction, and suggested a schema. She gave some examples to illustrate her analysis.

(1) Offering a prayer, she was thinking about Bill.

(2) Walking along the street, I met her.

(3) Offering a prayer, she went to bed.

(4) A lamp suddenly went out, leaving us in utter darkness.

(5) Looking back, she threw a kiss to me

In sentence (1), participle clause X shows the state offering a prayer, and main clause Y shows the state She was thinking about Bill. X and Y show the state at the same time (Figure.3). In sentence (2), participle clause X shows the state walking along the street, and main clause Y shows the event I met her. The event Y happens at some point during the state of X (Figure.4).

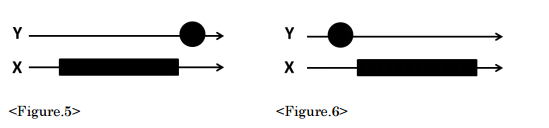

In sentence (3), main clause Y shows the event she went to bed, and the participle clause X shows the state offering a prayer. The event Y happens after the state X (Figure.5). In sentence (4), participle clause X shows the state leaving us in utter darkness, and the main clause Y shows the event a lamp suddenly went out. The state X begins after the event Y (Figure. 6).

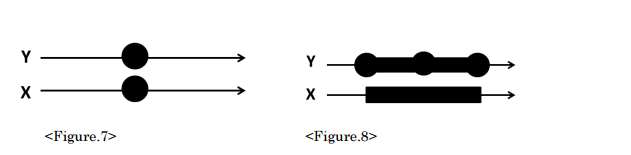

In sentence (5), participle clause X shows the event looking back and main clause Y shows the event she threw a kiss to me. These two events happen simultaneously (Figure.7).

To sum up, in all situations in her investigation, a main clause arises in the temporal range of the participle phrase (Figure.8). It follows from what has been said that we can find simultaneity between the main clause and the participle clause.

I found two problems in this study. For one thing, it didn’t examine what determines the meaning of participial construction sentence. What is more, it didn’t mention how Japanese use this construction in English.

3. Consideration

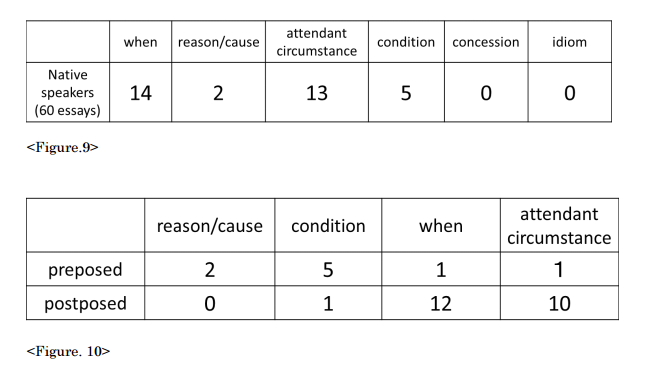

The purpose of this paper is to clarify how the meaning of participial construction sentence is determined and how Japanese students construe participial construction. In this research, I will classify the meanings of participial construction into 6 groups (when, reason/cause, attendant circumstance, condition, concession, idiom), following Sugiyama (1998).

3.1. Conditions which Decide the Meaning

To begin, we will examine conditions which determine the meaning of participial construction. To observe the problem, I collected examples of participial construction used by native speakers from CEENAS. 1

3.1.1. The Difference between Preposing and Postposing

First of all, we will classify the examples used by native speakers of English. (Figure. 9) In addition to this, I will examine that whether the participle clause is preposed or postposed. I divided them into two groups, “preposed” and “postposed”, to find the difference in usage. (Figure. 10)

1 In this paper, I use CEEJUS (Corpus of English Essays Written by Japanese University Students) and CEENAS (Corpus of English Essays Written by Native Speakers). Their topics are restricted to “It is important for college students to have a part time job.” and “Smoking should be completely banned at all the restaurants in this country.” In CEEJUS, the essays are classified based on the score of TOEIC.

We can observe from the table that the participle clauses which express reason/cause and condition are mainly preposed.

(6) Turning to the left, you will see a large building.

(7) Not knowing what to say, I remained silent. (Sugiyama 1998: p.417)

Sentence (6) is an example which expresses the meaning of condition. In this sentence, the preposed participle clause shows the precondition of the main clause.

Sentence (6) is an example which expresses the meaning of condition. In this sentence, the preposed participle clause shows the precondition of the main clause.

Another thing we can conclude from the table is that the meaning of when and attendant circumstance is mainly postposed. Looking at the examples of when, 11 sentences in 12 occurred with either the conjunction, “when” or “while”. This usage is idiosyncratic in participial construction because it specifies the relation between the main clause and the participle clause by using a conjunction. Therefore, it can be said that this usage is unusual for participial construction. Added to this, to look at the examples of attendant circumstance, 9 sentences in 10 express the meaning of soshite2. To take sentence (4) as an example, the state of the postposed participle clause (leaving us in utter darkness) arises after the event of the main clause (A lamp suddenly went out).

3.1.2. The Concept of Participial Construction

It follows from what has been said that the preposed participle clause makes ground of the postposed main clause by expressing the precondition. This is the main concept of the participle construction. As I examined above, the postposed participle clause sentences were expressed with the conjunctions, “when” or “while”. This is an unusual usage of the participial construction. Another example expressed by the postposed participle clause shows that it exhibits the event or state which arises after the event or state of main clause. These examples are not the central meaning of the participial construction which expresses simultaneity.

In fact, we could find some exceptions which are opposed to this concept. The sentence I was lying in bed, watching TV. (Watanuki, Petersen 2006 : p169) is opposed to the main concept of participial construction that we discussed above. Though the participle phrase is postposed, the state of lying in bed functions as the ground in this sentence. The condition that the preposed sentence makes the ground for the postposed sentence is not violated in this example.

3.2. The Participial Construction Used by Japanese Students

From now, we shall concentrate on how Japanese students construe the participial construction, comparing it with native speakers. We will begin with examining the differences in meaning. Then we will compare the usage of attendant circumstance. Finally, we will examine the difference of the usage of when.

3.2.1. The Meanings of Participial Construction

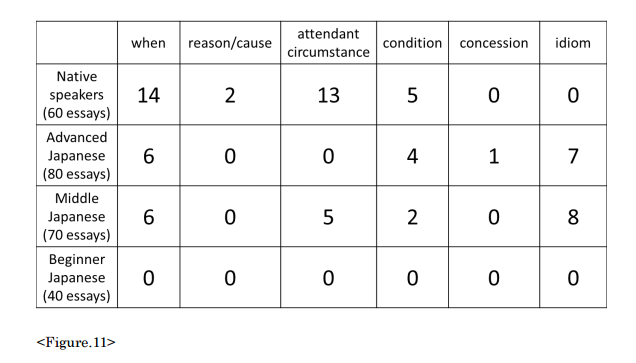

We shall now look more carefully into the meaning of participial construction as used by Japanese English learners and native speakers. I searched CEEJUS and CEENAS to find the difference in meaning used by native speakers, advanced Japanese students, intermediate Japanese students and beginner Japanese students (Figure.11).

2 “Soshite” is a Japanese word which is equivalent to “and then” or “after that”.

The table shows the classification of the examples found in the essays. As the table indicates, beginner students do not use participial construction in 40 sentences. It may be difficult for beginner class students to use participial construction.

We can also observe that Japanese students use idioms like “judging from” and “generally speaking” many times. I perhaps they use participial construction by memorizing idioms.

Finally, Japanese students also have a tendency of not using the meaning of reason/cause. Sentences which express reason or cause have what we would call a time lag between the main clause and the participle clause. Perhaps this is why Japanese students do not usually construe reason/cause participial constructions because they usually construe participial constructions when there is a strong simultaneity.

We will investigate the results relating to when and attendant circumstance found in the table.

3.2.2. The meaning of When

As shown in the table, we could find 14 sentences of time for native speakers and 12 sentences of when for Japanese students. Comparing the difference between native speakers and Japanese students, 12 sentences of the 14 by native speakers occurred with the conjunctions, “when” or “while” as in sentence (6). In the case of Japanese students, only 4 sentences occurred with the conjunctions, “when” or “while”. As I stated before, this usage is idiosyncratic in participial construction because it specifies the relationship between main clause and participle clause by using a conjunction. Therefore, it can be said that this usage is unusual for participial construction.

(6) It is important that universities consider this fact when setting course work, and should try to be flexible with lectures, meetings and such.

To sum up, native speakers express the meaning of when which shows the simultaneity by exceptional usage of the participial construction. In contrast, Japanese students express the meaning of when by central usage.

3.2.3. The Meaning of Attendant Circumstance

For the present, we will discuss about the meaning of attendant circumstance. In Sugiyama (1998), attendant circumstance consists of 2 meanings, nagara and soshite. I will take examples from Hayase (1992) to illustrate this. Sentence (1), “Offering a prayer, she was thinking about Bill”, expresses the meaning of nagara3. In this example, the state of the main clause and the participle clause arise simultaneously. Sentence (3), “Offering a prayer, she went to bed”, expresses soshite. In this example, the event “she went to bed” happens after the state “offering a prayer”. In this situation, there is a time lag between main clause and participle clause.

To find the difference of using attendant circumstance between native speakers and Japanese students, I looked at the examples of soshite and nagara usage found in essays. The data of native speakers shows that 9 in 13 sentences express a meaning equivalent to the word soshite in Japanese. Sentence (7) is an example which expresses the meaning soshite. In the case of Japanese students, I cannot find any sentences which express the meaning soshite in the 5 attendant circumstance sentences. We can see from this data that Japanese students don’t use the meaning, soshite, which has time lag between the main clause and the participle clause.

(7) Also, when people breathe smoke, it alters the taste of food, making it taste bad.

3.2.4. The Construal of Japanese Students

Let me summarize the main points that have been made in this chapter. In 3.2.1, we found that Japanese students don’t express the meaning of cause-result relation which has time lag between the main clause and the participle clause. In 3.2.2, we clarified that Japanese students express the meaning of time by central usage of the participial construction unlike exceptional usage which is mainly used by native speakers. In 3.2.3, we proved that Japanese students cannot express the meaning of soshite in attendant circumstance which has a time lag between the main clause and the participle clause.

All these examples make it clear that Japanese students can use participial construction sentences when the main clause and the participle clause arise simultaneously. However, they are poor at expressing participial construction which has a time lag.

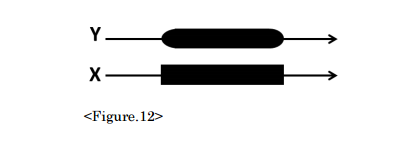

3.2.5. Hypothesis

We can assume from these analysis that participial construction, as used by Japanese students, has a different tendency from that of native speakers. The schema shows that participial constructions used by Japanese students (Figure.12) have strong simultaneity compared to native speaker’s usage (Figure.8). As I showed in chapter 2, Hayase (1992) suggested that main clause arises in the temporal range of the participle phrase. Unlike native speakers, Japanese students have trouble perceiving events that occurred immediately before or after the participle clause as being simultaneous.

4. Support

In this chapter, we will verify my hypothesis by offering supports from three aspects. In the first place, we will examine preposing and postposing of Japanese students. In the second place, we will check the simultaneity of participial construction used by Japanese students. Furthermore, we will inspect the relationship between the main clause and the participle clause.

4.1. Preposing and Postposing of Japanese Students

If my hypothesis is correct, Japanese students don’t care about preposing or postposing because the participial construction used by them has strong simultaneity. On the other hand, native speakers distinguish preposing and postposing to make the passage of time clear. For example, in the sentence He sent me a telegram, saying that he would arrive at ten, the event of the postposed clause happens after the main clause. I checked all examples to determine whether the participle clause is preposed or postposed. (Figure. 13)

What we could find from the table is that Japanese students use the meaning of when and attendant circumstance by both preposing and postposing unlike native speakers. The above proves the hypothesis is correct.

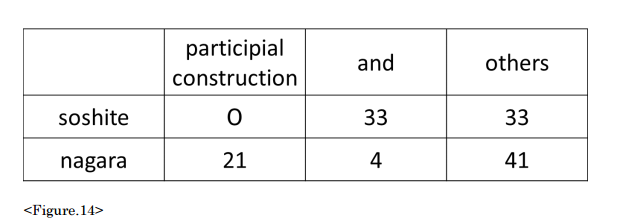

4.2. The Test about the Simultaneity of Participial Construction

From now, we will support our hypothesis by testing whether Japanese students use participial construction to express the meaning of soshite. I gave a test to a Japanese university freshman class. The class has 33 students. The content of the test is to translate Japanese sentences into English. I gave four Japanese sentences consisting of two soshite sentences and two nagara sentences. In the case of the soshite sentences, they didn’t use participial construction to express the meaning of soshite. In the 33 sentences, they used “and” instead of using the participial construction. The rest of the sentences are ungrammatical sentences or expressed with other usages. On the other hand, in the case of nagara, participial construction is used in 21 sentences. Four sentences are expressed with “and”, and the rest of the sentences are ungrammatical or expressed with other usages. (Figure. 14)

All these findings make it clear that Japanese students are poor at using participial construction which has a time lag between main clause and participle clause. In contrast, they can use participial construction when they express the meaning of nagara which expresses simultaneity. From what we discussed above, we could say that our hypothesis is correct.

4.3 The Test about the Relation between Main Clause and Participle Clause

For the present, we will support our hypothesis by testing the relationship between main clause and participle clause. I gave a test to another Japanese university freshman class. The content of the test is to translate English sentences into Japanese. I gave sentence (8) as a question.

(8) Her costume ripping open, she sang an aria.

There being no context, we could find the meaning of time, concession and attendant circumstance inconsistently in the answers. But this is not the problem in my research. Another thing we could find in the answer of the test is that some students could not make a distinction between the main clause and the participle clause. 20 students in 27 translated the sentences correctly. 7 students, however, translated the sentences, as shown in sentence (9).

(9) Singing an aria, the costume of the singer ripped open.

They didn’t care about the relationship between main clause and participle clause. We can assume that this can be explained by simultaneity of participial construction. They don’t care about preposing and postposing of participle clause because they construe participial construction as having strong simultaneity. The findings above verifies that our hypothesis is correct.

5. Conclusion

We may, therefore, reasonably conclude that the preposed participle clause makes ground of the sentence which expresses the precondition of the main clause. This is the main concept of participle construction. As far as the difference of participial construction usage between native speakers and Japanese students, participial construction usage used by Japanese students (Figure.12) has strong simultaneity compare to that of native speakers.

In fact, we could investigate the difference in using participial construction between native speakers and Japanese student. However, there is room for argument on how can we apply it to English teaching as a second language. We take up this question in the further study

References

Hayase, N. (1992). ‘Bunshikoubun ni okeru Figure/Ground sei ni tsuite no ichi kousatsu (A consideration on Figure/Ground nature of participial construction)’, Osaka Literary Review 31: pp. 10~22.

Ishikawa, S., Maeda, T., and Yamazaki, M. (2010). Gengokenkyuu no tame no Toukeinyuumon (A guide to statistics for linguistic reserch). Kuroshio publishers.

Ronald W. Langacker. (1987). Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Stanford University Press.

Ronald W. Langacker. (2008). Cognitive Grammar. Oxford university press.

Sugiyama, T. (1998). Eibunpou Shoukai (A comprehensive English grammar). Gakushu Kenshusha.Watanuki, Y. and Mark Petersen. (2006). Hyougen no tame no jissen roiyaru eibunpou(Practice royalEnglish grammar for expressions). Oubunsha.

Data Sources

CEEJUS (Corpus of English Essays Written by Japanese University Students)

CEENAS (Corpus of English Essays Written by Native Speakers).